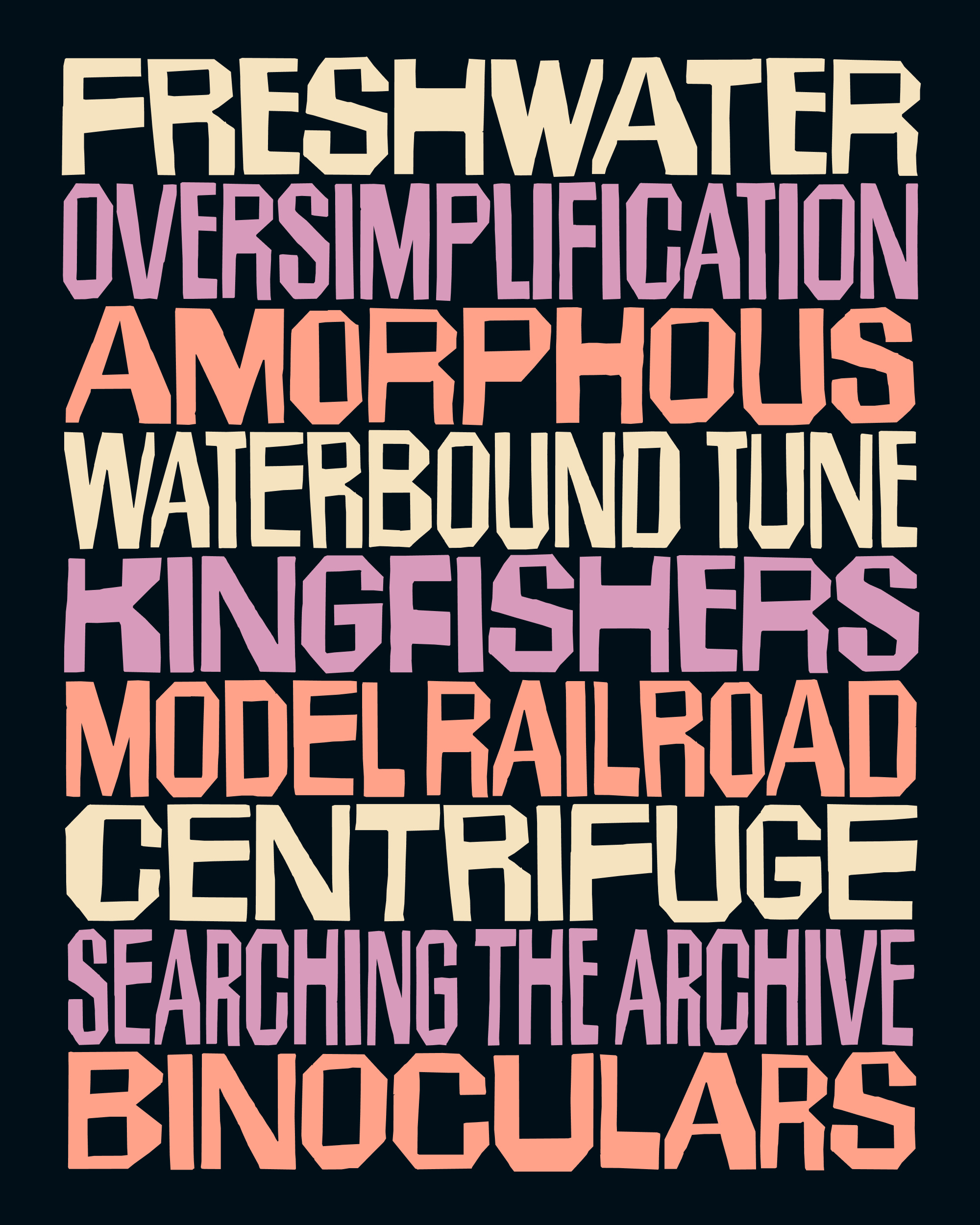

January’s Font of the Month: Bungee Widths

Last year, I sent you a story about how a squished use of my font Megavolt inspired me to make Megavolt Narrow. The moral of the story was that type designers should see stretching and squishing type not as a misuse, but as a challenge.

Bungee is my most widely-distributed font, and it has probably been squished more times than all of my other fonts combined. This wide distribution has put some distance between me and my creation—it was released and open-sourced nearly a decade ago, and I’ve barely touched it since. (Huge thanks to Just van Rossum and Marte Verhaegen, who did a big modernization and cleanup of the font files in 2024.)

Living in the countryside, I don’t get to see Bungee in action as much as my city-dwelling friends. But every once in a while I pass through a city and see it in the wild. After encountering some squished Bungee on a restaurant menu, I decided it was finally time to accept the challenge that was presented to me and draw some Bungee Widths.

Some lightly-squished Bungee on the menu at Tripoli. Photo by Nick Sherman, designer of the Bungee minisite.

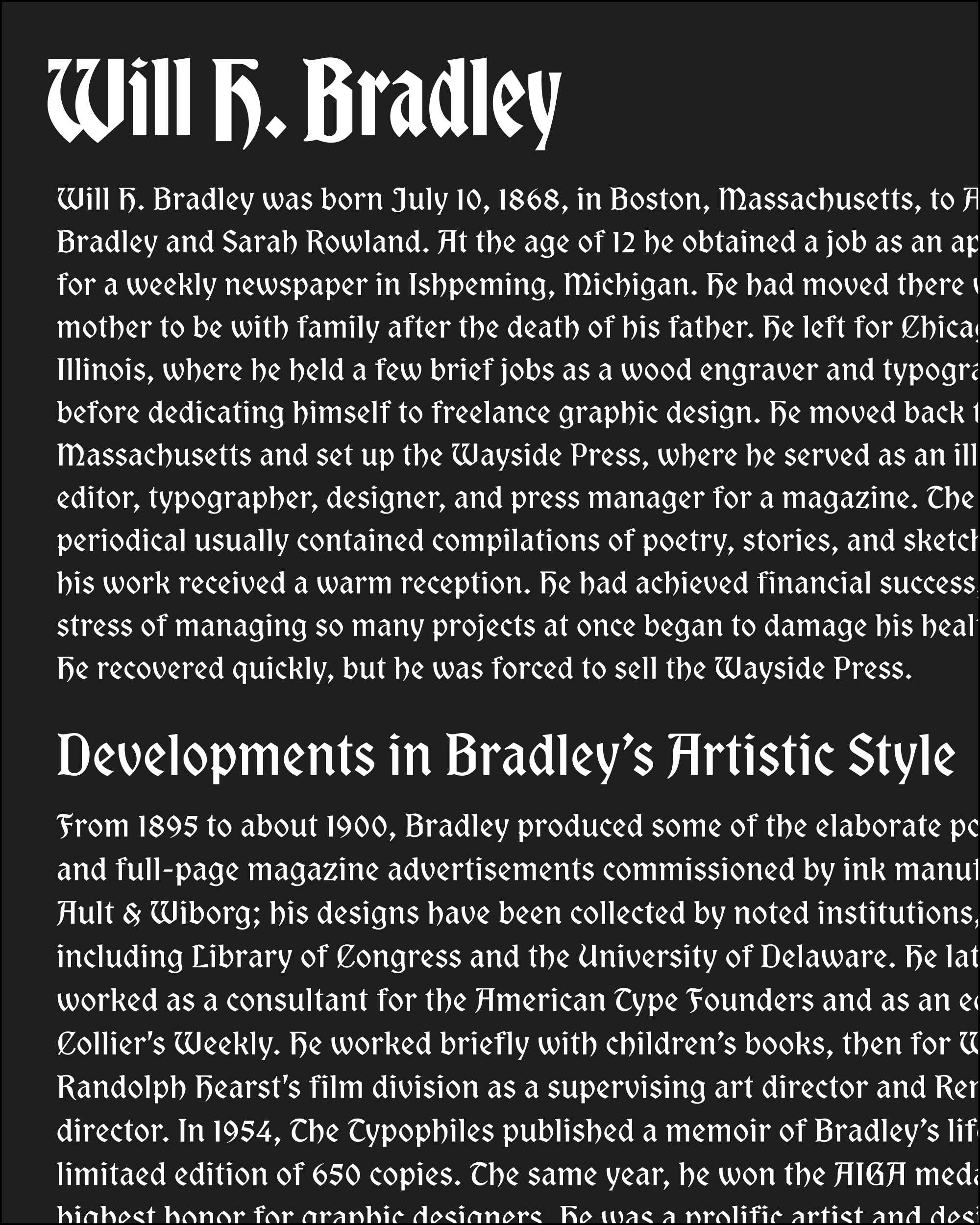

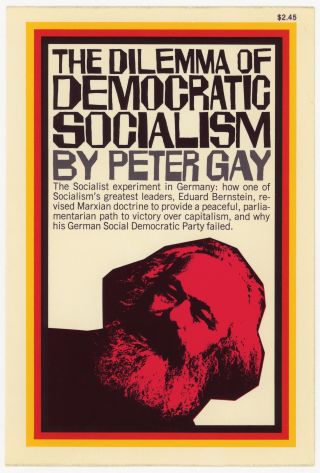

Bungee was inspired by and designed for vertical signs with stacked letters—its vaguely-monospaced appearance, straight sides, and distinctive serifs on I and L all stem from those origins. Even though the vast majority of Bungee uses are horizontal, I love that these little vertical details seep into each use of the typeface.

But let’s forget about vertical typesetting for the moment. Don’t get me wrong…I love a font with a gimmick, and I will choose a purpose-driven “gimmick font” over a general-purpose “vibes font” any day of the week.

But at a certain point, a gimmick font needs to transcend its gimmick and just be a font. Bungee has found its way onto everything from seltzer cans to sports programming to Pokémon books, and most of those users were not worrying about vertical text. And it has been refreshing for me to return to Bungee all these years later and not feel compelled to worry about it either.

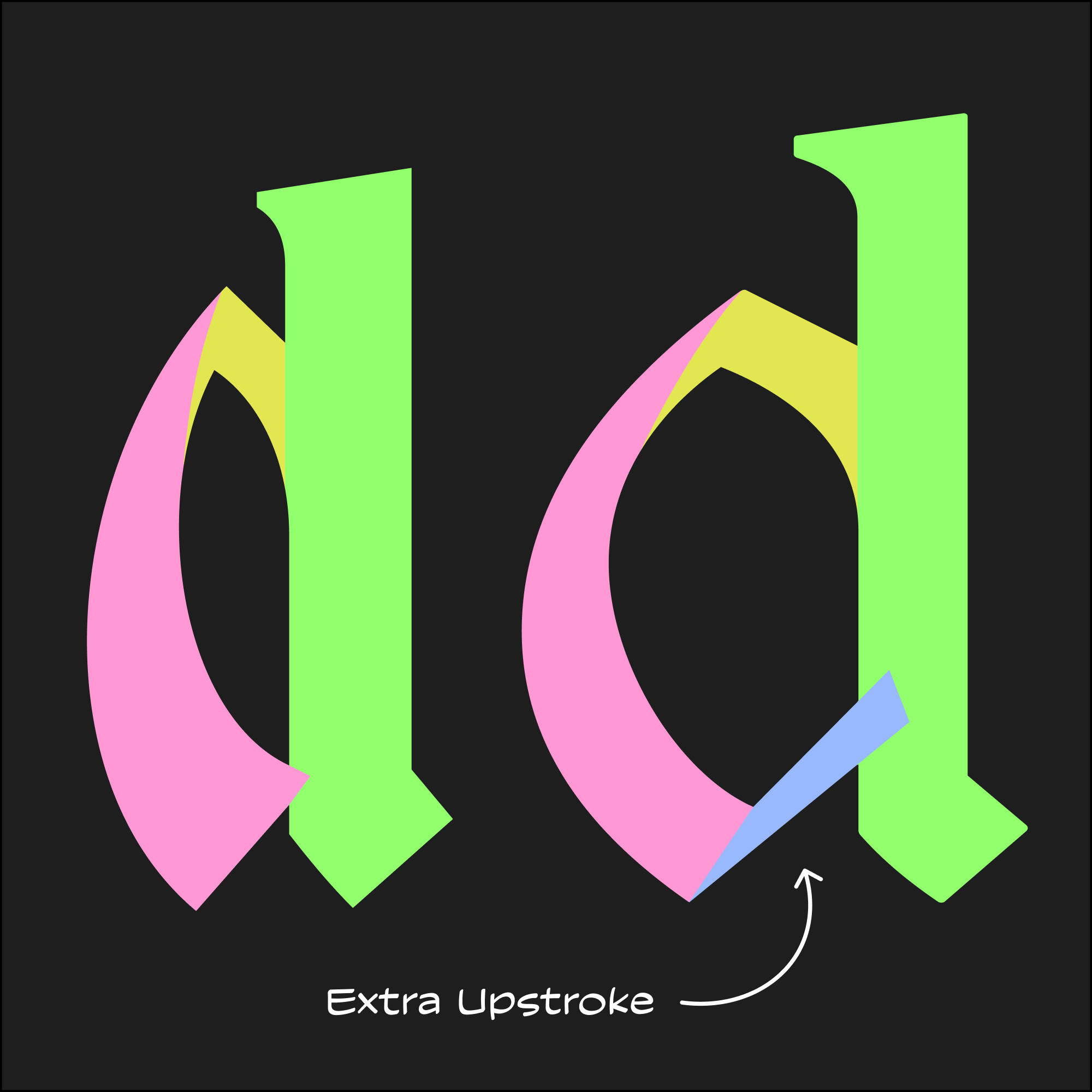

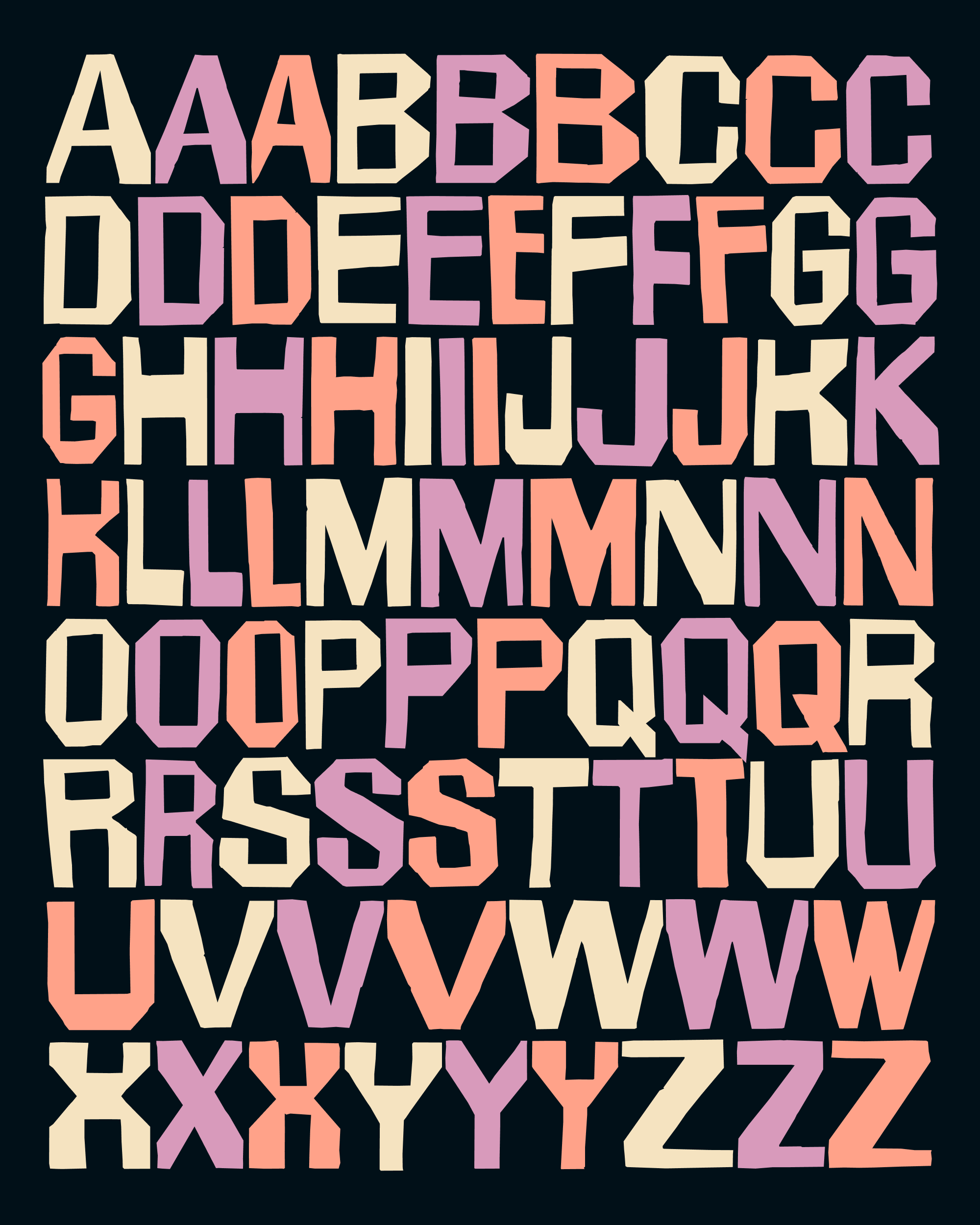

With straight sides and open apertures, Bungee had no trouble getting narrow. I started by over-squeezing each letter, down to about 40% of the original width. Then I added back the necessary stem thickness to the outside of the shape, widening it back to about 70% of the original width. Finally, I thinned out the horizontal strokes, elongated the vertical straight segments, and un-squished each curve.

While I was revisiting the design, I also played around with reducing Bungee’s rounded corners (now available as a variable axis) and tried my hand at a lowercase too (currently available in a separate font, only for the Extra Condensed width). I’m still not sure about the diagonal crossbar on that lowercase a!

It’s also worth noting that, like the original version of Bungee, these fonts come with the Open Font License rather than my standard one. I realize that it’s a little odd to send out a font to the club that is destined to be free, but if I didn’t do it for the club, it would never happen!

I hope that you still find some value in it, or that I can make it up to you in future months. And I hope it’s at least a little interesting to change up this aspect of the club…you can feel free to send Bungee Widths to friends, file issues on the repo, and even check out my source files if you want to. (Be warned: they are an unholy mess at the moment!)